The Path to Agility Part 5: When it still goes wrong

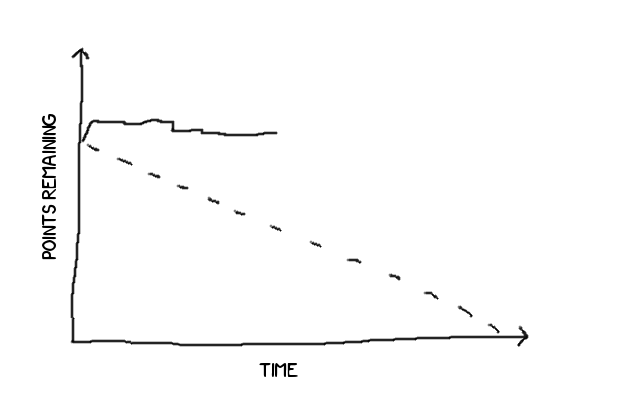

Last time we talked about a sprint whose burndown was going wrong, and the actions we took. One week later and our burndown still looked like this:

What now?

At this point we knew we were in trouble, we had external commitments which required us to have something to show at the end of the year - but even fixed time/variable scope projects don’t function when there is no burndown at all.

As it turns out, we still have options to help us recover - and in this situation I called a stop, wrote everything we were doing up on a white board, and tried to establish what work was outstanding and what was blocking progress. For us, it turned out that almost every story in the sprint had a requirement linked back to one other story, in other words we had a dependency that if we could just finish it would unblock almost all of the work and get us into a much better state.

We were desperate, so I decided to fly in the face of everything we’re taught about the mythical man month 1 and add developers to a late project. Because both myself and our product owner have a strong technical background we pitched in to help unblock the blocked stories.

Adding knowledgeable developers is not as bad as you would think

The core problem with adding developers to a late project is the resulting increase in communication required because the number of communication channels grows as the square of the number of team members. Developers not familiar with a project will also have significant knowledge hurdles to overcome before they can become productive team members, and thanks to Agile’s “documentation-light” philosophy there’s likely to be a significant amount of communication required at those early stages.

Fortunately, our product owner and I already have all the knowledge necessary to contribute to the development, we are (after all) heavily involved with the team and their work on a day-to-day basis. Even so, the increase in communication required when going from 4 active developers (on this project) to 6 was very noticeable. Scrum may suggest team sizes of 3-9 2, but our experiences on this project lead me to strongly favour sizes at the lower end of the spectrum.

The Analysis

Last time I said one of the most important things you can do is to analyse the failure. This is exactly what we did at the retrospective, we started by going round and having everyone say how they thought the sprint went - pleasingly not everyone said “terribly”, some of the failings were obvious but there were also some positive points around the knowledge gained and the way the team worked together as a whole.

We then broke out into a more unusual activity, a sprint time line. A time line consists of two parts

- Have everyone write down the events they remember on different coloured

post-it notes (or your favoured medium). The colours correspond to:

- Good events

- Problematic events

- Significant events

- Have everyone mark how they were feeling at various points of the time line (I went with happy, neutral, and sad faces).

The idea is to build a shared record of what happened, when - and how it affected the team.

There were a few things that became obvious from this activity:

- Our failure was right at the beginning of the sprint, between the sprint planning on Friday and kicking off the sprint on Monday there was a significant shift in how the team planned to implement the work. This was exacerbated by a number of people being on holiday on one day or the other, and a lack of suitable subtasks that would have clued us in to the fact that we had changed the implementation to one that wouldn’t fit in the time available.

- Our interventions (restarting the sprint, adding developers) were generally viewed positively, but ultimately could not overcome the hidden scope change.

- Unsurprisingly, the team felt pressured and stressed for the majority of the sprint

Overall, the activity was very time consuming - and I’m not convinced I would do it every retrospective, but the shared view of what went wrong was very useful.

The Actions

Having identified problems, the next step is to identify concrete actions we can take to prevent those problems occurring again.

We have regular “planning and estimation” sessions with our product owner to help estimate and forecast upcoming stories. We decided that after these sessions we would take some time, either in individuals or pairs, to add subtasks to stories planned for the next sprint. We want these subtasks to be sufficiently detailed that any team member can take on the work.

We also said that if there’s not a subtask for it, we should be questioning whether or not we should be doing it.

Finally, we decided to stop using “As an X I would like Y so that I can Z” for the titles of our stories. While this kind of title captures the whole story, it makes it almost impossible to grasp the state and content of a sprint at a glance, instead our PO will try to write brief descriptions that are easier to take in quickly.

These two changes should help to tackle the problem from two directions, we should be more easily able to see a high level overview of our progress - and use that information to spot discrepancies in the high level, feature work. We should also be able to spot discrepancies at low level, technical work, thanks to having pre-planned subtasks.