Refactoring

Refactoring is something that you hear about almost constantly in software engineering these days. Agile practices centred around minimal documentation and avoiding big up-front design drive a need to constantly reduce any accumulated technical debt in order to maintain the “sustainable pace”. In this post I wanted to talk a bit about my views on the practice.

What is refactoring?

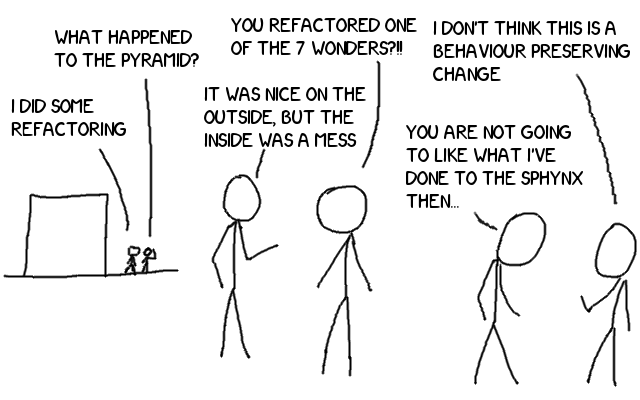

Refactoring is the process of changing a software system in such a way that it does not alter the external behaviour of the code yet improves its internal structure 1

The key idea here is that we’re making some changes to the internal structure of the code (to improve it), but we are confident that we are not making changes to the behaviour. How can we be confident that we have not changed the behaviour? Because we have behaviour driven tests that prove the behaviour has not changed.

What if we don’t have tests? Then we are not refactoring! We can’t be sure that our changes won’t take a working system and break it, so we shouldn’t be making the change. The only refactoring we can do in this case is to add tests since adding tests cannot change the behaviour (assuming your test and production code are separated

- if not then you have problems my rambling is not going to help you with!).

Why refactor?

Since our changes do not affect the product at all (by definition) you might ask “why refactor?”, since there is no tangible benefit for the customer - why invest resources in refactoring at all? The answer lies in the idea of technical debt. There are multiple definitions of technical debt, but the one I like is the one by Steve McConnell:

[Technical debt is] a design or construction approach that’s expedient in the short term but that creates a technical context in which the same work will cost more to do later than it would cost to do now (including increased cost over time) 2 3

In other words, technical debt describes a characteristic of a software system that makes future work more expensive. When we refactor, we are attempting to eliminate these characteristics so that future work will be cheaper.

There are many sources of technical debt, many of which can never be eliminated. Two in particular are a lack of up-front knowledge and the fact that technology tends to evolve over time. Technical debt caused by lack of knowledge occurs because we almost always learn more about the requirements of a system and the best way to build it as time goes on. Technical debt from the evolution of technology occurs because the most expedient design or construction today may not be the most expedient design or construction in a years time. This last is surprising, because the debt can suddenly “appear”, one day you’re working with version 4 of a library and doing things in the most efficient way - the next day version 5 is released and suddenly you’re sitting on a pile of debt because the approach of using version 4 means you can’t use the more time or cost efficient methods from version 5.

Other definitions of debt focus on debt incurred as a result of a business decision to take an expedient approach in the short term in order to meet some deadline or other requirement. I don’t like these definitions because they imply that the only source of debt is these decisions, when in fact there are other sources that all have the same effect of making future work more expensive.

When to refactor?

Not all debt is worth refactoring to remove; all debt can incur a cost of development at a later date - but it only does so when we’re working on code that is affected by the debt.

This makes the answer obvious - tackle debt in the components you are working on, when you are working on them. There’s no benefit in addressing debt in a rarely changed component, the “interest rate” is so low as to be negligible. Conversely, a component that’s touched frequently needs debt tackling aggressively, as it has a comparatively high interest rate.

One last thing to watch out for when deciding when to refactor - look out for your own vanity. It’s surprisingly easy as a developer to decide to refactor someone else’s code because it’s “not how you would have done it”, but the reality is, when you do this you have to be sure you are making the code better. Sometimes (and I’m as guilty of this as anyone), we’re not making the code better - we’re just making it different.

Tracking debt

The technical backlog is an established best practice to define purely technical work packages 4. This is effectively how we are managing the debt in our system, whenever we encounter an aspect of the system that is slowing down development, we log it as a technical debt task. We let the product owner prioritise and schedule these tasks the same way all our other backlog tasks are scheduled - subject to the usual rule that the planning meeting is a negotiation between the product owner and the scrum team.

In this way we keep track of what debt we have in the system, and align tackling the debt with the development work we are doing in any given sprint.