On Testing Part 3: Goals of Automated Testing

In this part of my “On Testing” series I talk about what I believe the goals of automated testing are, and how they influence how you should write tests.

Goals of Automated Testing

OK, so by now you probably think you know the answer to this…right? Most people will probably say something like “the goal of testing is to build confidence that the software works as designed”.

Wrong. Well…kinda, that’s obviously the goal of testing, but is it the goal of automated testing? I think we need to make a small change:

The goal of automated testing is to build confidence that the software still works as designed.

One word. Big difference. To understand it, we need to understand the difference between regression testing and non-regression testing. Regression testing is about testing that something that used to work, still works. Non-regression testing is about testing that new functionality works as designed. Obviously you’ll write automated tests for both, but the key thing to observe is that as soon as you ship the new functionality, the non-regression test becomes a regression test by definition. So, all automated tests are regression tests and must be written as such.

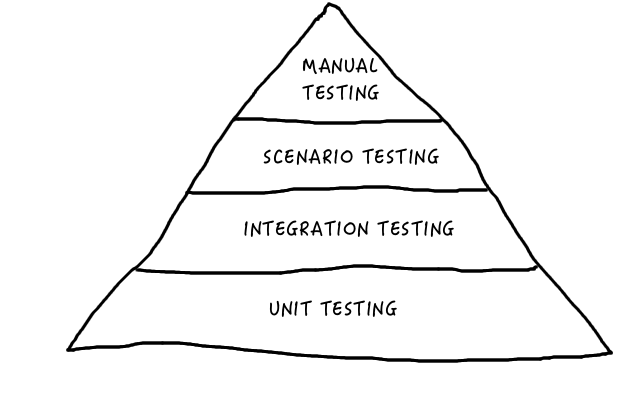

So what’s special about regression tests? Well, the idea is that when you make changes to the code, either to refactor it or to add new functionality, the regression test proves that (at least so far as the test suite is concerned) nothing has changed. This is important because when tests are built in layers, the results of each layer depend on the results of the previous layer. As I discussed in the previous article, we build tests in a kind of pyramid:

When you modify a test, you invalidate any conclusions built upon it…now, perhaps you can revalidate the test for trivial modifications through code review, but if you need to make complex changes to the test you’re out of luck. Any conclusions built on top of the original test are invalidated when the test changes significantly, and all that testing needs to be done again if you want to have the same level of confidence that things work as you did before.

In order to meet the goal of automated testing, we need to write tests that will survive the test of time, we need to write tests that won’t change when we refactor or add new functionality. If our tests are too closely tied to the implementation they will be fragile, and therefore be no use as regression tests. In short, we need tests that test behaviour, and not implementation 1.

This may sound obvious, but look at a lot of tests and you’ll see that people often confuse testing the implementation with testing the behaviour. However, the implementation can change for many reasons - but the behaviour only changes when someone decides the old behaviour was wrong. If we’re testing behaviour, then we’re testing the thing we’re ultimately interested in - and that’s a great way to make sure your process is working right.

Levels of test

The need to write tests that survive code changes is one of the reasons unit tests are profilic and popular. Unit tests, by their very nature, are robust to changes in other elements of the system - but this leaves us with a problem - because the lower you go, the less “behavioural” you get, the less the tests tell you about how well your program as a whole is working. Again, as discussed in the previous article, we need to make sure we cover the whole spectrum when trading off coverage and complexity.

The thing is, it doesn’t matter where your tests sit in that spectrum - every point on this line is a useful part of the whole test suite, and the more tests you have the better your coverage is. This leads to a simple principle, that should cut out a bunch of futile discussion about how to structure tests: pick points in the test spectrum which let you write the most robust tests in the least time, don’t get hung up on which class of test you’re writing. So if you have a test that is kinda a unit test but interacts with some other components that are hard to mock…don’t sweat it.

Understanding failures

Jay Fields recently did an interview on SE radio 2 where he talked about some of the most important elements of writing tests. Specifically, he offered three pieces of advice (I’m paraphrasing here, listen to the interview and draw your own conclusions!):

- Delete tests that aren’t useful

- Get rid of loops in your test cases

- Get rid of shared set-up and teardown (make tests self-contained)

The first point can easily be applied to what we’ve learned so far - if a test is brittle, it’s not meeting the goal of automated testing and we can delete it. If a test is testing implementation and not behaviour, then, again, it’s not meeting the goal of automated testing and we can delete it.

The second two pieces of advice are interesting though - because they’re not touched on by anything I’ve discussed so far. These two pieces of advice are about what happens when tests fail, and boil down to one basic idea:

We should build self contained tests that clearly state what is being tested, what has failed, and why, and nothing more.

This has a really interesting interaction with conventional software engineering. The average software engineer tries very hard to avoid duplication of code, but this advice goes directly against that - we should avoid repeating code and factoring out duplicate blocks! This is practically heresy! But pretty much the first time you come to debug a failing test case all will suddenly become clear - when you spend more time tracking your way through the “refactored” test code than the actual product code you will immediately see why it is crucial that a test case clearly expresses everything relevant to the test.

This is ok because, as long as we write tests that test behaviour, then we don’t need to change the tests unless the behaviour changes. A change in behaviour implies that all the code that depends on the changed behaviour might be broken, so a full audit of all the dependent code (triggered by the failing tests) is actually a necessary part of the development process.

Next time, on “On Testing”

In this article I introduced what I consider to be the two objectives for someone writing automated tests

- The goal of automated testing is to build confidence that the software still works as designed.

- Tests should be self contained, clearly stating what is being tested, what has failed, why, and nothing more.

Next time, I’m going to talk about a framework that helps us to meet these goals called “behaviour-driven development”.

-

If an implementation test covers interaction with some external component, than it can be a useful way to test that any changes in the external component haven’t broken the implementation. Still, such a change should really also be visible in the behaviour, so the absence of such an implementation test is not a critical problem. ↩

-

SE-Radio Episode 256: Jay Fields on Working Effectively with Unit Tests ↩