On Testing Part 5: Agile

So far in this series I’ve talked about automated testing. Automated testing is an essential part of what makes sprints viable - because in order for something to be releasable it needs to work, and in order to know something works we (usually) have to test it. Thus, everything I’ve written so far is very useful in Agile environments. In this article I want to touch on the place I think manual testing has in these environments.

So far my career has had me working in relatively small teams, often without any dedicated testers - this means that most of my experience is with what I believe doesn’t work. This post is collection of my thoughts on ways that manual testing could work with Agile.

Misconceptions

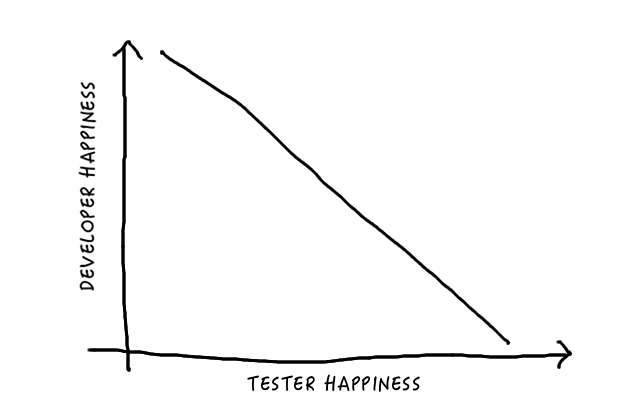

One misconception I’ve come across that seems particularly damaging to an agile environment is the idea that a tester’s only purpose (other than making programmer’s lives miserable) is to test.

One of the base principles of Scrum is that there are no specialised roles, that doesn’t mean there can’t be specialists - it just means the specialists can do more than one thing. Nowhere is this more obvious than with testers. If testers stick to their “one thing”, then for a reasonable chunk of the start of the sprint they will have nothing to do because nothing is finished yet. This is obviously wrong, how can it be day 1 of a sprint and a team member has nothing to do?

The Secret Waterfall

One solution that seems to come up often is the idea of staggering development and test sprints. In “Succeeding with Agile” 1, Mike Cohn is fairly dismissive of this solution:

If the testers work one sprint behind the programmers, who will they go to when they have questions? Will that be efficient for the programmers in the sprint? Will the testers be able to effectively take part in the sprint if the rest of the team is discussing how the next round of features should be added while they are testing the ones added already?

This part of his argument is about efficiency, sprints are meant to be focused work periods for the team with minimal distriction. It is fairly self-evident that the testers cannot complete their work without involving developers - so splitting the work like this damages the sprint.

Another argument Cohn makes is that hand-offs are bad - any time we are handing off work we are reducing collaberation, reducing shared responsibility, and adding a communication and documentation burden to the team. This is against the philosophy of agile, and is why staggering development and test sprints is suboptimal.

The Mini Waterfall

If we’ve established that testing needs to be done in the same sprint as the development work, then the next most tempting solution is to have developers hand-off to testers as and when they finish their stories. We’ve already made the argument that hand-offs are undesirable in an Agile environment, but this technique generates its own, additional problems.

Firstly, the test team has little or no work to do at the start of the sprint, which is clearly suboptimal. Secondly, the tendency will be for the developers to hand over all the stories in the last few days of the sprint, leaving no time to actually test them. As a result, the stories are not “done” and the product is not shippable. The failed stories end up carrying over to the next sprint, which creates difficulties during sprint planning - as the stories need to be re-estimated, kept as they are, or ignored. In turn this makes the sprint itself less focused, as bug fixes on stories from the previous sprint trigger interrupts in the stories in the new sprint. The effect builds from one sprint to the next and triggers a kind of cascading failure in the way sprints are planned and executed that causes the agile environment to become dysfunctional.

There has to be a better way.

The Half-Way House

Jim Bird gives a nice summary of the concept of “Hardening Sprints” 2. In this model, we accept that testing during sprints will be incomplete and instead dedicate some time (let’s say a sprint) to “hardening” the product prior to launch.

In some cases this will be because certain kinds of software just can’t be tested without some kind of manual intervention (usually when hardware is involved). More often though, this is the result of an organisation transitioning to Scrum that may not have sufficient automated test coverage and so finds that the manual test burden during the sprint is simply too high.

If you’re working this way I would encourage you to look at why a hardening sprint is necessary, and whether investing time in test automation would allow you to use that time to develop useful features instead.

The Agile Tester

To see how to correct this we need to understand a bit more about a tester’s role. In my view, there are two major components to testing:

- To complete a functionality “check list” that confirms each piece of the software is working.

- To understand the requirements of the customer and validate that the implementation meets those requirements.

If we look at all those activities we can actually pick out four tasks, two of which don’t require any development at all:

- Understand the requirements of the customer

- Prepare a functionality “check list”

- Complete the functionality “check list”

- Validate the implementation

Straight away we can see activities the testers can be performing around understanding the initial requirements and fleshing them out. This is a natural phase near the start of the sprint, where the user stories and Mike Cohn’s “Conditions of Satisfaction” are expanded into more concrete designs. These activities will likely have to be done in tandem with the programmers who are working on the features, the expertise of the tester in understanding how customers will utilise the software can be brought to bear in active discussions on how best to implement the feature.

- Understand the requirements of the customer

- Work with developers to expand the story details into a more complete design

- Prepare a functionality “check list”

- Complete the functionality “check list”

- Validate the implementation

In fact, we can do better - in Scrum there are no specialised roles, and automated testing is king. We don’t have time to repeat the “functionality check lists” every sprint so we’re going to need to automate them. This sounds like an ideal activity for the team members with expertise in testing to complete. Let’s add it to the list.

- Understand the requirements of the customer

- Work with developers to expand the story details into a more complete design

- Prepare a functionality “check list”

- Write automated tests for the functionality check list

- Complete any manual elements of the functionality “check list”

- Validate the implementation

Even though the list above is ordered, the work is not fully sequential - rather, the agile tester continuously performs these activities throughout the sprint. The tester engages in exploratory testing of the new features as they are developed. This leverages the tester’s greatest strength - a deep understanding of the software and how the users use it. By integrating testers directly into every phase of feature development they can offer this feedback much sooner, increasing not only the reliability but also the quality of the features that are delivered at the end of the sprint.