The Path to Agility Part 2: No-one teaches code review

I do weekly one-on-one meetings 1 with everyone on my team. I do this because, with hindsight, a regular opportunity to relieve myself of frustrations and blockers, and to talk about where I wanted my role to go next is something I’ve wanted in every job I’ve had. It’s perhaps arrogant of me to assume what I wanted is what my team wants, but I do it anyway - the meetings are not for my benefit, they are for and about helping my team with whatever might be bothering them that week. I do it every week because the only way to get in front of a problem is to know about it as soon as possible. We still do sprint retrospectives as a team, because day-to-day we function as a team - but people are different and I find the conversations I have one-to-one are markedly different to those we have during the retrospectives.

Code review

Why do I bring this up? Well partly to ruin the “preview” on the feed page of this site - but more because when I did my one-on-ones last week I found the majority of the team talking about how we’re doing code review. My answer was the same to everyone - we’ll discuss it at the retrospective and decide as a team how we can make things better.

Something I’ve noticed during my career is a lot of people do code review, and yet nothing in our programmer skill-set prepares us for what is necessary to be good at code review. Without this preparation reviews often get caught up in minutiae and personal preference 2.

There are plenty of people who will give you checklists for what to look for in a code review 345, and there is a reasonable amount of good advice out there as well. From my personal experience the following guidelines are probably the most useful:

- Review the right things, let tools to do the rest

- Everyone should code review

- Review all code

- Adopt a positive attitude

- It’s OK to say “Ship it!”

- Keep the code short

- Ask for the author to walk you through the code for anything substantial

So what are the right things to review? The checklist idea comes up a lot, but I think there are only two things to look for:

- Correctness, and,

- Maintainability

Correctness encompasses a lot of things, and certainly you can make lists of all the things you would like to check to ensure the code is correct - but if we start from the point that we need to look for things that are fundamentally wrong, cases where the code won’t work then we can make a decision about whether or not any comments we are adding are adding value, or just a counter-productive use of time.

I say this because code reviews are expensive, code reviews that have an unnecessary back-and-forth are extremely expensive. We have to remember that each comment is an interrupt for the author of the code, a context switch from their current task back onto the review code, and a series of chores to checkout the relevant code, make the changes, test those changes, and push the updated review. If you’re making a comment on a code review you need to be sure that the benefit outweighs the cost of responding to it.

Correctness is, for the most part, mandatory - even in cases where code has an intentional caveat we need to make sure limitations are, at the very least, documented.

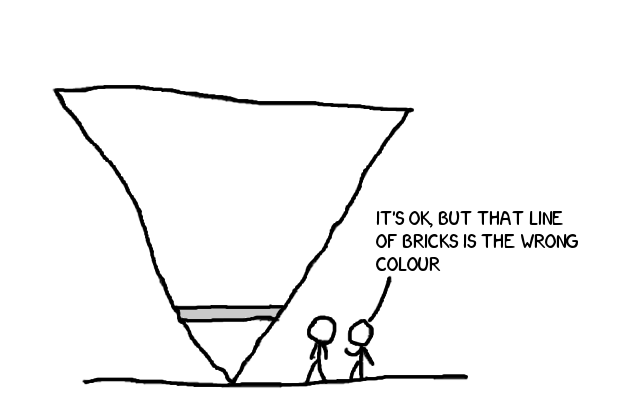

The other aspect of code review is maintainability. Again, we can make a list of things to look for - but now our list is more complex, because there’s another factor at work and that is the cost of the change. We need to be sure that the cost of the debt outweighs the cost of the change we would make to tackle the debt. This is the standpoint I would argue from when I say that commenting on formatting in a code review is wrong the vast majority of the time. It is something I might do for a new starter during their probation, simply to help educate them to the standards and conventions of the code base they are working with - but it is not something I would do with someone more experienced. Many coding conventions include some get-out clause along the lines of “if it makes your code look bad, feel free to ignore the guidelines”, so if an experienced developer is breaking convention it’s probably a concious choice and you should trust their judgement on the issue.

So how can we make decisions about maintainability? We need to consider the scope of the impact, is it limited to a line? A function? The file/module? Or beyond? Generally I would consider any maintenance impact outside the source file/module as needing to be corrected, for example:

- Is the interface easy to use correctly and hard to use incorrectly?

- Could users of this interface trigger subtle bugs?

- Is the interface documented?

- Is the overall architecture documented?

- Does the interface violate the principle of least astonishment?

- Are the test cases complete?

- Are any existing contracts being broken?

- Is code or functionality duplicated?

Maintenance impact within the source file or module often needs to be corrected, for example:

- Do any of the above apply to functions private to the file or module?

- Does each part of the implementation do one thing? Does it obey the SOLID principles?

- Is the file or module small enough that someone can reasonably keep the entire structure in their head at once?

- Can you understand what the code does and why it does it relatively easily

However, with file and module level issues we know that the impact of the debt is restricted to that module - so we can consider how often we think the module is to change when deciding whether or not to tackle the debt immediately or defer it until we next need to change the module.

In general, I worry much less about issues that only impact a function and not at all about issues that affect a single line. For the most part all I would worry about is:

- Can you understand what the code does and why it does it relatively easily?

- Is the function written in a way that means changes could lead to subtle bugs?

These lists are not exhaustive, or prescriptive - when reviewing for maintainability we need to keep in mind the golden rule that the cost of paying off any debt must be less than the cost of living with it. Remember the Agile principle that “Our highest priority is to satisfy the customer through early and continuous delivery of valuable software.”, we must take a pragmatic approach when redoing work otherwise we risk being unable to deliver valuable software.

What we used to do

Our version control is Mercurial, but our workflow is “inspired” by Git - we typically work in personal forks of the main repository and then use Rhodecode’s pull request mechanism to open a review.

Rhodecode’s pull request mechanism is quite limited, although we can set default reviewers (so that everyone gets notified that a new pull request is open) Rhodecode requires that at least half the reviewers have reviewed a request before it can be submitted. We work around this by deleting excess reviewers once a couple of team members have had a chance to look over the changes.

Once a pull request is approved we locally rebase the revisions onto the head of our main development repository and push, where-upon our continuous integration will pick up the changes, build them and run the automated tests.

We didn’t have any particular guidelines on who should review code, or how, or what kinds of things to comment on and look for.

What we do now

In our retrospective I asked four questions:

- What should we review?

- Who should review it?

- How do we decide when a review can be closed?

- What should we look for in a review?

Initially when discussing what should be reviewed the feeling was that everything should be, however, after some discussion it emerged that some changes (such as helper scripts) can be difficult or unnecessary to review because they’re not what I termed “stakeholder facing”. We decided that any code which influences the end product needs to be reviewed, but other changes can be reviewed at the author’s discretion.

The answer to “who” should do reviews surprised me, prior to the retrospective I’d viewed reviews as a means to ensure quality first and a method of disseminating knowledge second. On this basis I’ve always assumed that only one person should review code, because reviewing for quality is time consuming and suffers from diminishing returns as more people become involved. The team felt that one of the main benefits of reviews was to share knowledge about the changes being made to the code-base - as such, they felt that everyone should be able to review all changes.

We settled on using Rhodecode’s built in support for flagging that a review is in progress as a way of indicating that a team member would like to review the changes. To keep the time burden down we also distinguished between doing an “in-depth” review for quality, and a “superficial” review for knowledge.

We split closing reviews into two activities, firstly, we decided that only one “in-depth” review was required before changes can be merged to the main development branch - but we also decided that the author can explicitly request additional in-depth reviews for code they are not confident about. For small changes it is acceptable to grab another developer and have them eyeball the diff to avoid the overhead of creating a pull request for trivial changes.

To close the review itself, it needs to be merged and no reviews are allowed to be “in-progress”. This is simply to allow others to complete their reviews and add any comments before an “approved” review is closed.

One issue that several team members mentioned is that it is difficult to tell whether a reviewer’s comment is intended as a requirement in order to pass the review or a suggestion. Delving into this, there was a feeling that there are different “levels” of comment reflecting how severe the reviewer felt the problem is. After listening for a while we realised that we were essentially describing the MoSCoW method. We decided that we would annotate comments with this “common language” to help communicate how important certain changes are.

The last question I asked is what we should look for, unfortunately the retrospective was near the end of our timebox so we probably didn’t look at this in the depth I would like. There was a general feeling that the team felt that all comments are useful no matter how trivial, as long as such comments were appropriately annotated.

This is the first time I’ve run a retrospective focused on one particular aspect that seemed to be bothering the team. Overall, I’m pleased with the results - I think we had a productive discussion about how we do review, and agreed on some helpful changes. I’m also pleased that the end result is not what I would have implemented myself, as this means that the team is genuinely engaging with how our department is run!