The Path to Agility Part 4: When it goes wrong

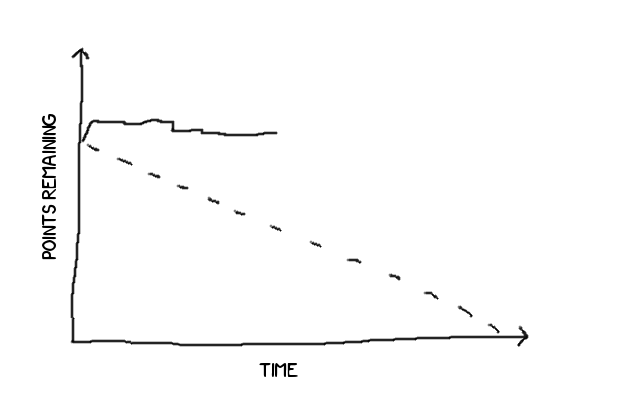

It’s Monday morning, the start of a new week and half way through your sprint. Your burn-down looks like this:

What do you do? Should you have done something sooner?

There are actually a lot of ways a burn-down can end up looking like this, and only some of them are because nothing is getting done. Off the top of my head:

- This happens with “mini-waterfall” cultures where work is constantly handed from one step to the next throughout the sprint. When one of those steps is a bottleneck (for example, the test team is too small), then work accumulates in that step without making progress.

- This happens when the team is working as a collection of individuals and the sprint contains a small number of large tasks. Everyone picks one large task and spends the entire sprint working on it. At the end of the sprint you tend to get an all-or-nothing cliff in the burn-down.

- This happens when the tasks are just too big. Unsurprisingly, a sprint that contains one massive task is going to have a step function for its burn-down chart.

- This happens when the team is stuck on technical issues, for example, if you don’t have a “sprint zero” to create the infrastructure for a project then the team might spend a lot of up-front effort creating the infrastructure before they get to the value-added work.

- This happens when there’s a dependency blocking completion of work. We try to minimise dependencies when writing stories, but sometimes they’re unavoidable - a dependency within a sprint can block progress on many tasks.

- This happens when something has gone horribly wrong.

- This happens when no-one is working (for example, everyone decided to take a holiday and you failed to account for that when scheduling the sprint).

Don’t panic

It’s OK for things to go wrong occasionally, so firstly don’t panic. As soon as you realise something is going wrong in the sprint it’s time to start communicating, with the team and with the stakeholders. Grab the team and the product owner and sit down to talk about how best to manage the situation.

The first item on the agenda should be figuring out what’s gone wrong, in our case we were starting a new mini-product and had significantly underestimated the cost of setting up the infrastructure work.

Once you’ve established the cause of the problem it’s time to choose a solution. At this point you basically have three choices:

- stick your head in the sand and blunder on regardless,

- replan the rest of the sprint based on what you’ve learned so far, or,

- abort the sprint and plan a new one.

The first option is unlikely to yield helpful results, but it seems to happen surprisingly often. The second two are about re-arranging the work you have to make sure you’re delivering value - you need to look at what’s been done so far and work out what can be finished by the time the sprint ends. Alternatively, it might be that so little “sprint” work has been done, or the work has turned out to be so far outside what was originally planned that it might be best to abort and re-plan. Aborting a sprint is always something to avoid, it breaks the cycle and will wreck all the estimation, planning and expectation management the product owner has been doing - but sometimes, it’s the best option.

In our case the team decided that the vast majority of the unplanned infrastructure work was now done, and the original sprint was viable if we restarted it. With the Christmas break looming we decided that it would be better to abort the current sprint and spend one full sprint getting the minimum viable product done

Analyse the failure

Once the sprint’s back on track make time at the next retrospective to analyse the failure. Looking at the work we planned, it’s clear to me now that we didn’t think through the tasks thoroughly enough. We failed to do subtasks for a lot of elements. For other elements we didn’t consider full vertical slices through the system, and yet other tasks were altogether missing (yet obvious in hindsight). This is my mistake, because I didn’t look over the sprint in detail and allowed the sprint to be started with insufficient planning. Obviously this will be a talking point for our next retrospective, but already I can see that if we commit to creating subtasks and making sure the subtasks represent a full slice through the system we’d be in better shape next time we take on a project like this.