The Path to Agility Part 7: Slicing

Lately I’ve been spending a lot of time thinking about slicing work. This article is about my struggle with it.

Vertical slicing

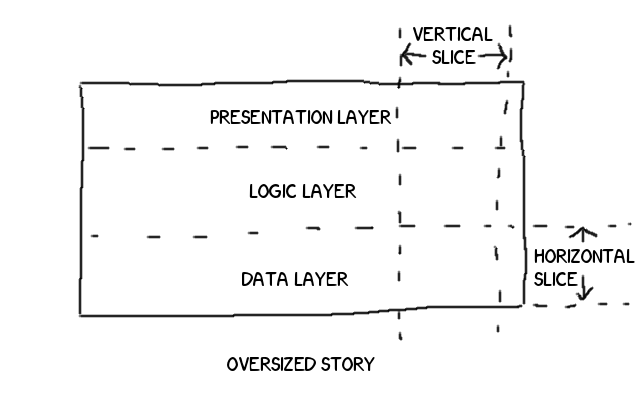

As a software developer one of the concepts I find most difficult to apply is vertical slicing. My brain, equipped with many years of development experience, naturally sees the horizontal splits in the system, the traditional “layers” we find in a multi-tier system where we try to split features into a data layer, a business logic layer, and a presentation layer.

The problem is, as someone trying very hard to be agile this is the wrong way to slice a system. If we go all the way back to the first of the Agile principles we have the following:

Our highest priority is to satisfy the customer through early and continuous delivery of valuable software 1

The implementation of the data layer is not valuable software. The implementation of the business logic is not valuable software. Even the implementation of the presentation layer is not valuable software. It is only when we have all three that we have valuable software.

Vertical slicing is about taking a story and simplifying it in one or more of the horizontal layers instead of splitting it along those layers. The extension from the simplified work to the original intention becomes a new story that can be prioritised separately.

How to create vertical slices

Richard Lawrence describes a number of patterns for splitting stories 2, and even offers up a helpful little cheat-sheet for applying those patterns 3.

The core idea is to find simplifications of a story that allow the the complex elements to be de-prioritised or deleted. It’s best to read Lawrence’s original material, but for the lazy here’s a quick summary of his patterns:

- Split workflows by doing the beginning and end first, then enhancing with the middle later; or by applying other patterns to the individual steps of the workflow.

- Split out operations, for example a typical CRUD (Create, Read, Update, Delete) interface could be split into four stories - one for each operation.

- Simplify business rules - look for flexible or vague language in the requirements and simplify the story by tying down the language to specifics. Look for business rules are are adding complexity and try to move them to separate stories.

- Split out different input data. Simplify the story by implementing one type of input data first, then enhancing with other types of data later.

- Simplify the interface. Sometimes an element will have a complex UI - split the story into a simple UI and enhance it with other stories later. If there are multiple ways to do the same thing, build one interface first and add the others on later.

- Look for the “obvious split”. The “Independent” part of the INVEST rules sometimes makes the obvious split difficult, for example we often have stories to implement a report with several variations. The obvious split is into the various reports - but the first report will be harder than the others because it will have to build most of the scaffolding. We can split this story into a “implement one of X,Y,Z variations” story and a “implement X,Y,Z given one is already done” story. The stories are not truly independent, but we are at least making the dependencies minimal and explicit.

- Remove complexity. Some stories are a simple core with most of the value, and a series of complex requirements built on top. Build the core first.

- Defer performance. Sometimes stories have performance requirements that make them hard, in this case build the story first without the performance requirement; then enhance it with the performance requirement later.

- Create a spike to reduce uncertainty. Sometimes the reason something is hard is because there is a lot of uncertainty. Often the easiest way to reduce uncertainty is to build something valuable first then use the knowledge gained to define the future stories. Failing that, we will need a spike to reduce the uncertainty. With the knowledged gained from the spike we can better estimate or split the original story. This is a last resort, because a spike is a research task which won’t deliver valuable software. One thing I cannot emphasise enough is to define the outputs of the spike and hold the team to them. It’s easy to get lost in research and overrun a timebox, spikes need to be small, well defined and focused otherwise they will fail to reduce the uncertainty.

How to know if you created a vertical slice?

This is actually pretty simple; can you give a build to the test team and have them test the new feature? Saying “test nothing changed” does not count; that is literally the definition of refactoring and a waste of your test team’s time. It doesn’t matter whether or not you have an actual test team, at the end of the day someone probably needs to test something - whoever it is needs to be able to test that the changes are correct. If the answer is no, then you probably created a horizontal slice.

The other question to ask is “could you accidentally ship it?”. Again, if the answer is “no” you probably didn’t create a full slice through the system. Sometimes compromises need to be made in order to have a vertical slice that is accidentally shippable (for example, dropping a performance requirement might introduce the need for a simple “busy” or “progress” display).

That’s it for now, next time I want to introduce some practical, real world, examples of slicing.