The Path to Agility Part 8: Retro

What’s the most important Scrum meeting? Is it the stand-up? That’s the most frequent meeting, the main synchronisation point for the team. Without the stand-up we might all end up working on the same thing, we might fail to collaborate on a story and end up with two mismatched halves, someone might be stuck and we would never know!

How about the demo? Without the demo how will our stakeholders know what we’ve done? How will we gather feedback on the product? How will we demonstrate working software?

Maybe it’s the planning? How will we know what’s valuable and what isn’t? When will we have the opportunity to clarify requirements? How can we make commitments to our stakeholders without it?

Does any of the above make sense to you? If so, then I’m sad to say, you’re mistaken. The most important Scrum meeting is the retrospective, for one simple reason, if anything is wrong with any of the above meetings, or any other aspects of your development process, the retrospective is your opportunity to fix it. Without this period of introspection, problems and impediments may go unaddressed for long periods of time or even indefinitely. The retrospective is also the only meeting that can fix itself if it’s broken. If you’re going to put all your effort into getting one meeting right, then put it all into getting the retrospective right.

It probably won’t surprise you to learn, then, that the retrospective is the only Scrum meeting directly codified in an Agile principle.

At regular intervals, the team reflects on how to become more effective, then tunes and adjusts its behaviour accordingly.

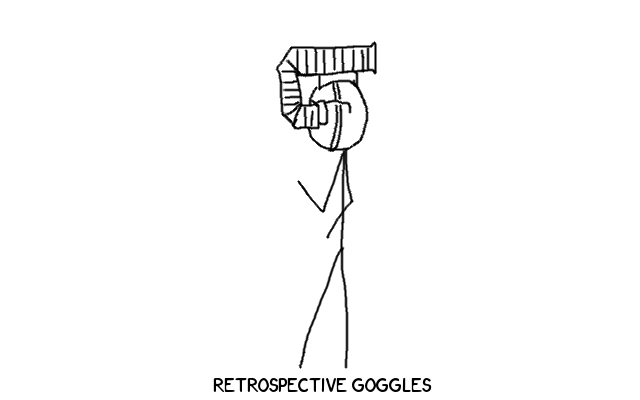

In fact, retrospectives are not just applicable to the Agile software world, they are useful wherever you’re looking to do continuous improvement.

How to retrospect

It’s the end of the sprint again, and there’s a meeting in the shared calendar for the 2 hour “retrospective” from 10am to 12pm. At five past ten the Scrum master has to go and remind everyone that they’re supposed to be in the meeting room now. Over the next ten minutes the team trickles in, perhaps with some protracted effort to dial in team members who are working remotely.

Eventually everyone is gathered around a large meeting table. The room is slightly too hot, because, as usual, the meeting room is really slightly too small for the team it accommodates. The Scrum master pipes up, “OK everyone, lets go round the table and everyone can answer the three questions -

- What went well?

- What could have gone better?

- How can we improve?

let’s start with Fred.” Fred looks briefly startled, he was working on a bug before the meeting, and his brain is still trying to work through what might cause it. He wasn’t really paying attention, but he eventually gathers himself and says “Um, I can’t really remember what happened last sprint…I guess…the thing that went well is that we got the Jingly Jangly feature done. It could have gone better if we’d managed to get it tested during the sprint. I don’t know how we can improve on that - it’s just not possible to test code until we’ve finished developing it!”. The meeting carries on in much the same vane, with most people offering vague or similar statements to Fred - apart from the one guy who takes copious notes, and reels off a list of complaints long enough that no-one can remember the first thing he said by the time he gets to the last.

Does any of this sound familiar to you? Does this sound like a meeting you want to be in? It seems pretty clear that in this fictitious scenario the team isn’t excited to join the meeting, the environment isn’t comfortable and the content is uninspiring.

I suspect that something like this is common among small and inexperienced Agile teams. When I first heard those three questions I thought they were a great idea. We can focus on the good along with the bad - and then come up with some real actions we can take to improve! This will be great. Some six or seven years after I started trying to work in an Agile way I see my mistake, in fact, I would go so far as to say that that format is poison to the Agile retrospective. It seduces you into the idea that that is all that you need - when in fact a retrospective needs a lot more to be effective.

Esther Derby and Diana Larsen literally wrote the book on Agile retrospectives 1. In it they set out the 5 basic phases of a good retrospective:

- Setting the stage

- Gather data

- Generate insights

- Decide what to do

- Close the retrospective

Setting the stage

Did the example above strike you as focussed? Did it seem like the team had a goal in mind? In Derby and Larson’s model the first part of a retrospective is to set the stage.

Setting the stage creates the context and atmosphere for the retrospective, so there are a few of things we might want to do here:

- Outline the rules of the retrospective, from the time box to the prime directive:

Regardless of what we discover, we understand and truly believe that everyone did the best job they could, given what they knew at the time, their skills and abilities, the resources available, and the situation at hand.

-

Set the focus, perhaps the team above might want to focus on how they test if their stories are not really done because they are not tested.

-

Set the mood, for example, a very common activity is to ask everyone for a one or two word description of how they felt about the last sprint. This has the added bonus of helping to trigger memory associations that will be used in the next stage.

Gather data

What’s the first thing Fred said? “Um, I can’t really remember what happened last sprint”. If you’re hearing that in your retrospectives, then you need to beef up this part. Gathering data is all about helping people to collectively remember the last sprint, and to construct a common narrative about what happened. Gathering data is based on facts, not opinions. One example of a way to do this is by creating a timeline.

Generate insights

In our example meeting do you see any analysis of the things that could have gone better? We jump straight from “what could have gone better” to “how can we improve” without asking why things weren’t as good as we’d like them to be. To decide on the most effective actions we really need to do some analysis of the problems first.

This phase is about taking the facts and identifying trends, themes and root causes. If we look at Fred’s answer again (poor Fred), he said “we got the Jingly Jangly feature done” - this is a fact (well, assuming their “definition of done” does not include testing). But why did Fred consider that a good thing? Was there something specific about that feature that meant completing it was significant? What did we do that meant that the feature got done when it otherwise might not have done?

One common activity for this area is to ask “five whys”, it is the most basic technique one can apply to get to the root cause of a problem. The idea is to keep asking “why” until the root cause is uncovered, the trick is to ask the right why - sometimes a response will yield multiple avenues, and it requires real knowledge of what the team was doing at the time to ask the “why” that will yield an actionable cause.

Decide what to do

Again, going back our our example meeting, it looks like there are actions - after all everyone gets to come up with some! I bet there is even some discussion as the team goes around the table of what those actions should be, and at the end of the meeting the Scrum master probably has a big list written down. Are those actions really team commitments though? Does it seem like the process is likely to identify the two or three best actions the team can take to improve the process?

In the most self explanatory phase of the retrospective, the goal is for the team to decide on some concrete actions to take during the next iteration. In fact, Derby and Larson use the term “experiments” for some actions, implying that the team should not only come up with an action, but design a way of measuring the consequences of that action.

If you have the same problems every retrospective this is the part to beef up, because the actions you’re taking are not having the desired effect. If you’re having difficulty following through on actions this is the time to build a plan and get team members to commit to following through on it.

The best actions are ones that will happen automatically as part of the team’s day to day work. For example, committing to do more pair programming is easy because pair programming is often part of the normal day to day. On the other hand committing to write documentation for a poorly understood part of the system may not yield results if writing documentation for legacy code is not part of anyone’s day-to-day. When actions generate work that is not the norm it is important to make sure time is allocated in the iteration to carry out those actions.

Close the retrospective

Closing is used for a few different purposes, obviously when closing you need to summarise the actions, and the commitments made. It’s also a great time to do a round of “appreciations”, where team members can appreciate the little things other people have done to help them out. Finally, it’s a good time to do a “retrospective retrospective”, to figure out how to make retrospectives more useful and productive in the future.