On Testing Part 2: The Test Pyramid

Carrying on the testing theme, in this article I’m going to describe “the test pyramid”. The test pyramid is a way of thinking about how tests relate to one another - and how they support building quality software.

Types of Test

As a fledgling test developer you’re going to hear a lot of terms, unit testing, integration testing, smoke testing, regression testing, scenario testing, and so on and so forth. And you’re probably going to hear a lot of phrases like “that doesn’t belong there, that’s an integration test not a unit test”.

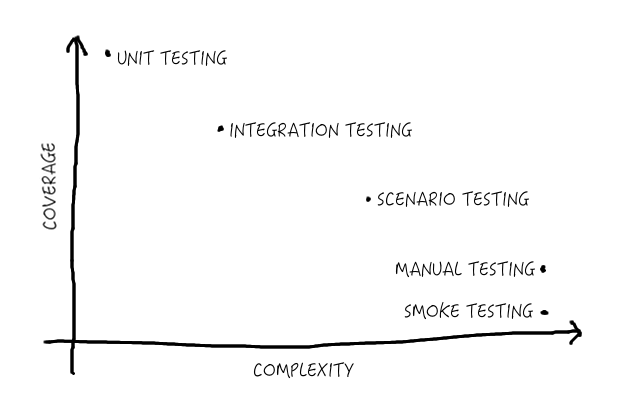

My advice? Don’t get hung up on the terms, there are really only two variables that matter when you’re writing tests - and they’re on a continuum, it just so happens that some people feel a need to classify parts of that continuum into particular categories of test. What matters is:

- How many different combinations of stuff need to be tested to cover every reasonable scenario (“complexity”)?

- How much of that space am I going to test to satisfy myself everything works (“coverage”)?

Here’s a chart:

Notice how the types of testing follow a trend - the more complex the thing you’re testing, the less you manage to cover the realistic scenarios. There’s nothing much in the bottom left - simple things are easy to test comprehensively, the only way you end up down there is if you’ve written bad tests. I’m sure you’ve also spotted there’s not much in the top right, there lies a fantasy land with unicorns, rainbows, and pots of gold that you will never reach. Any sufficiently complex system is practically impossible to test completely, the only way to get close is by combining layers of testing to build up confidence across the system. Lastly, it’s worth noting that automated smoke testing (where you run simple tests against the basic scenarios to check for obvious failures) is a poor man’s form of manual testing. A smoke test can only ever test what you taught it to test, manual testing (usually) involves people smart enough to spot errors that aren’t part of what they were testing.

The Test Pyramid

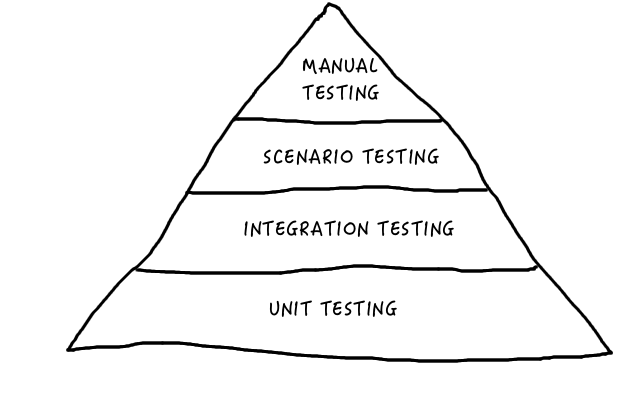

So how do we build coverage of the whole system? Well, traditionally we would divide the system into small units, and comprehensively test the units. Then we would test the interactions between units, there’s a combinatorial explosion that goes on though - so we confine ourselves to a smaller set of interactions. Then we combine even more units together for useful blocks of functionality, and we test some scenarios - behaviours close to how a real user would use the system. Lastly we can use manual testing and smoke testing to check that what we ship seems reasonable.

Generally, you will have a lot of unit tests - it’s easy to cover a large proportion of the system that way. At the next tier you’ll have a reasonable number of integration tests, maybe covering key interactions between services. Above that you might test some specific scenarios, either using large, useful, parts of the system, or the whole system. Finally, there’s a layer of manual testing at the tip of the pyramid.

At each layer the “cost” or “complexity” of the testing goes up, so you simply can’t afford to have as many tests - but the “coverage” of the whole system goes up as well, so, although you have fewer tests each individual test is more useful.

The idea of a test pyramid isn’t new, Mike Cohn talks about it in Succeeding with Agile 1. Essentially, it says you should have many more low-level tests than high-level tests because as you go up the pyramid the tests become most costly, more time consuming to write, and more brittle.

There’s one additional property of the pyramid that’s not obvious at first glance, we assume that if the results of the lower layers are valid, then any previous tests at the higher layers built upon that work are still valid. Now, obviously, with automated testing it’s easy to re-run the test cases (all be it time consuming)…but what about manual testing? A new feature probably receives significantly more attention during test than an old one, so long as our tests haven’t changed, the pyramid lets us make this distinction with confidence, because we can say that the behaviour of the old feature is unchanged as far as the tests are concerned.

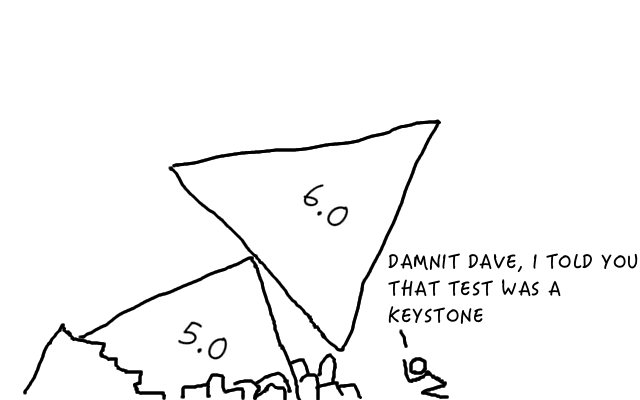

In this way, the base of the pyramid is actually composed of all the testing we’ve done on earlier versions of the software.

As long as our tests are static, over time we accrue a significant foundation of testing that gives us confidence that our products are getting better and better. Of course, if our tests are not static then all bets are off - which is what I’m going to talk about in Part 3: Goals of Automated Testing.