The Path to Agility Part 6: Burndown

In the last couple of parts of this series I’ve been talking about how we’ve been coping with sprints that went wrong. This time I want to look at a sprint that appeared to go right.

The burndown

Anyone familiar with Scrum will know about burndown charts. The basic idea of a burndown chart is to plot effort remaining vs. time up to the “commitment”. The are various different commitments we can track (by project, by release date, by epic, or by sprint) - but for the purposes of this post we’re interested in the sprint burndown.

There are also various ways we can track effort remaining. The obvious one is to track the number of story points that have not been completed, but there are others - such as counting the number of subtasks remaining, or constantly re-estimating the number of hours work left in a task.

To decide how to plot the burndown, we need to know what it’s for:

- To empower the team to take action when the sprint is off target (finding ways to unblock themselves when behind, and new work to take on when ahead).

- To enable the Scrummaster to detect and address impediments early in the sprint.

- To enable the Product Owner to pro-actively manage stakeholder expectations and alter sprint scope when necessary.

- To help analyse the team’s performance during the retrospective when looking for ways to improve.

- To communicate progress to stakeholders.

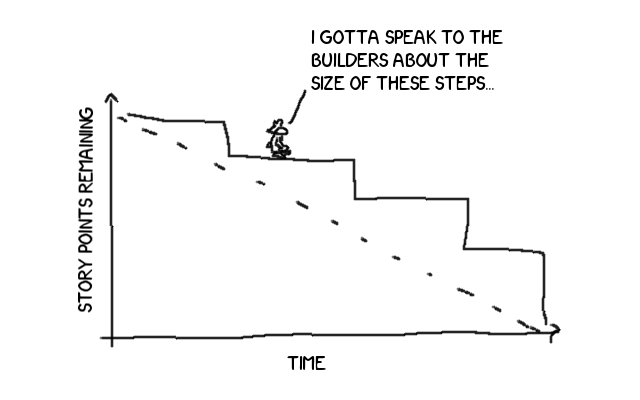

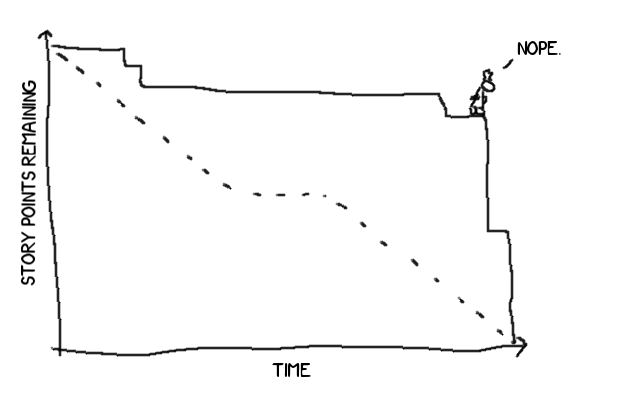

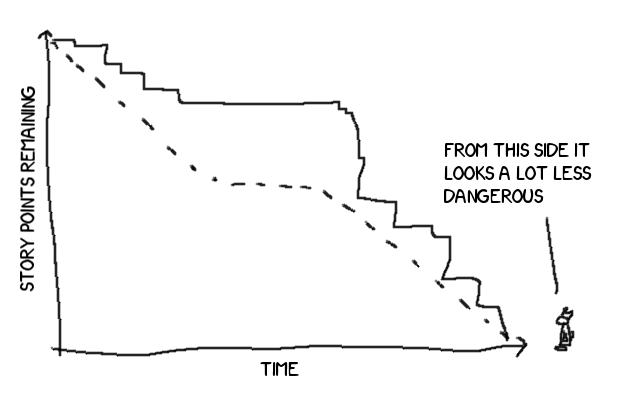

If we look at these we can see one common trend: it’s about knowing whether or not the sprint is on track. If we plot by story points, and have a relatively small number of stories with a large number of points in them then our burndown will be stepped, like this:

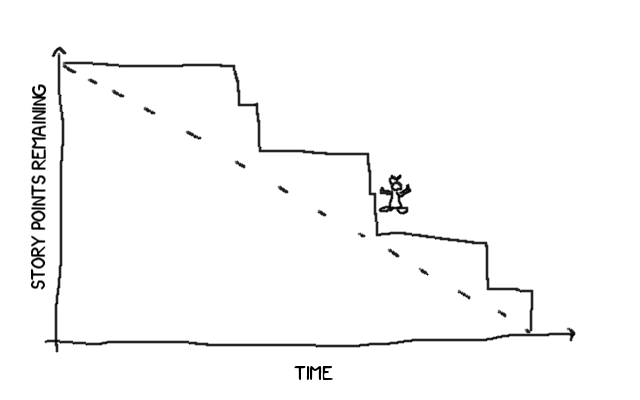

In fact, it could be worse, because if those stories are tricky to split between multiple team members then we may end up with a chart like this:

While just looking at completed stories is what matters to the product owner and the stakeholders, it’s not a realistic view into the progress of the sprint - the only time it will be useful for taking actions during the sprint is when we have a large number of stories with few points attached which is not always practical.

There is, however, one case where we do want to only look at completed stories - and that’s when we’re trying to minimise our “work in progress”. In particular, since we consider “working software” to be the primary measure of progress we need to make sure the team is finishing stories as soon as possible.

So, we need to look at both story points completed and effort remaining, but we want to focus on the latter for most purposes because the granularity of the former can make it difficult to interpret.

The real world

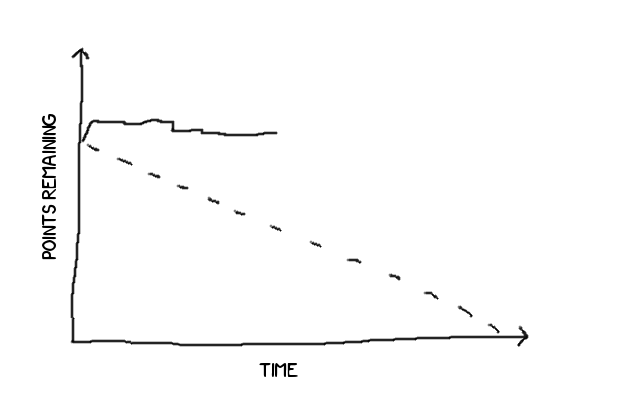

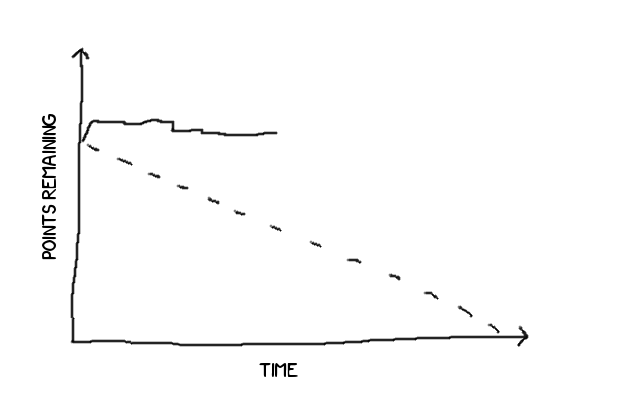

Remember in the last couple of posts in this series we looked at a sprint that wasn’t burning down, half way through the sprint the burndown looked like this:

Fast-forward to our most recently completed sprint, and half way through the sprint the burndown looked very similar:

This time though, I wasn’t worried - because I knew that around 80% of the work in the sprint was made up of two stories, and by looking at the subtasks I could see progress was being made. At the end of the sprint our (story) burndown looked like this:

In the retrospective we looked at this and could clearly see that the burndown wasn’t a true reflection of the progress we were making on these difficult-to-slice stories. We decided that we’d divide story points equally between subtasks, and look at that instead. In fact, the story points aren’t even that important - simply counting the subtasks remaining produced a very similar burndown. The “effort” burndown looked like this:

This isn’t a brilliant burndown, but compared to the previous sprint it’s a lot closer to what we want. There are, however, two features we should be concerned about - the first is that cliff near the start of the second week - clearly something stalled progress around that time and we should look at what that is. The second is the significant increase in velocity (the gradient) in the second week. Like a stall there are many reasons why this might be - but the one that should really concern us is whether or not corners are being cut to meet the deadline. If they are then we have probably incurred some technical debt that we will have to pay off later.

The positives

We got all our work done, through a combination of not allowing bugs raised against the previous sprint to affect the scope of the current sprint and by generating a decent set of subtasks to help divide the work.

The negatives

It turns out, we did incur debt toward the end of the sprint - something that we’re paying for in the current sprint. We knew this when we planned the sprint, so we set a sprint goal around ensuring the product was in a releasable state. This means the team can modify the scope of the sprint to meet the goal, rather than being torn apart by the twin forces of the need to add new features or to fix old ones.

Our actions

- Carry on generating decent subtasks

- Track our effort burndown more closely to better detect problems